US History of Reproductive Freedoms for Disabled People

by Maddie Fowler, DSHN YAB Coordinator

Image description: Illustration in the style of a black silhouette of a person posing in a wheelchair with one arm bent over their head, sitting up straight to accentuate the curves of their body. Behind the wheelchair is a black zig-zag print pattern.

Image source: (Holdsworth, 1992)

Introduction

People with disabilities in the US have faced a long history of discrimination and abuses in many areas of life, and including their sexual and reproductive freedoms. This history has set the stage for the way our society looks at sexuality education for disabled people today, and in fact many of the historical practices of discrimination are still present today, while often in a different form.

In order to promote sexual health for people with disabilities, we need to know about and work against our country’s history of eugenics. Eugenics is the idea that our world would be made better if certain minority groups (such as people with disabilities, racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, low-income people, and others), were not able to reproduce and have children. Work for sexuality education strives against eugenics and seeks to empower people with knowledge of their rights and how to stay healthy and find pleasure in their relationships. We must learn about history so we do not repeat it.

Eugenics and the word “Normal”

Much of the history of sexual freedom restrictions in the US has come from the idea of eugenics. Eugenics is the idea of “improving the human race” by only allowing certain groups of people to have children. This idea has been around since the times of Plato, but was defined and made popular in the mid-1800’s by Sir Frances Galton (statistician), and the theory of Social Darwinism, which was adapted from the scientific studies of Charles Darwin (Galton’s cousin) (Eugenics | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica, n.d.; Kliewer & Drake, 1998). Charles Darwin’s work proposed the idea of “survival of the fittest,” a theory that in the evolution of the natural world, organisms with traits that help them reproduce are more likely to pass their genes and traits on to the next generation. This idea, however, was very wrongfully transformed into “Social Darwinism,” by saying that certain groups of people receive the most power in society because they are innately better and more “fit.”(Evolution: Darwin: In the Name of Darwin, n.d.) These ideas of Social Darwinism and eugenics would be accepted across society, including by scientists, politicians, feminists, and many others, and were used to justify ableism, racism, imperialism, and social inequality (Eugenics, 2012).

Eugenic ideas have deeply influenced views and vocabulary in our society that is still used today. Before eugenics, the word “normal” did not have the powerful meaning it has today, but was used mostly as a technical term in math and carpentry. “Normal” was first associated with “regular/healthy” by Galton in the 1840’s, who wanted to influence people to conform to the “ideal” eugenic population. Nowadays, normal has come to inflict a lot of damage in our society, where many people think that they have to look a certain, “normal,” way in order to be valuable (for example, media influences us to believe that unhealthily skinny bodies are the only “normal,” and children with disabilities in school who are not considered “normal” are often bullied). The word “eugenic” was later coined by Galton in 1883, and then became popular through the widespread use of social Darwinism (Davis, 2013).

Ideas of eugenics were used in society to target and discriminate against many different marginalized groups, and to paint them in an unfavorable light. Eugenics was used to argue that disabled people, low-income people, racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, LGBTQ+ people, and other groups were bad for society and should not have children. Through these ideas, these marginlized groups were falsely associated with criminality, sexual vice and moral wrongdoing , and often grouped together in poorhouses, institutions or prisons (Eugenics, 2012; Eugenics, 2012; Kliewer & Drake, 1998). These eugenic views influenced many efforts to control disabled people’s reproductive freedoms.

Image description: Photograph of a round copper medal that was given in a eugenics competition. The metal has engraved text that reads, “Presented by American Eugenics Society Fitter Families Contest.”

Source: (Eugenics, 2012)

Early US History

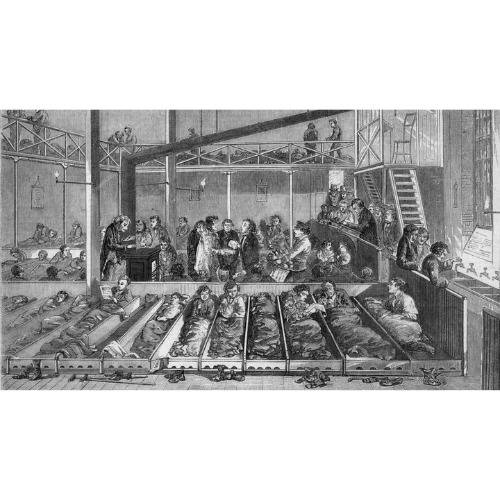

Throughout early US history, disabled people were often incarcerated and segregated from society in jails or poorhouses, and later poor farms. In the 1660’s, the first poorhouse opened in the US, a segregated, overcrowded and unsanitary, warehouse-like lodging where marginalized groups like disabled people and the poor were forced to live and work. (Action for Access - Changing Perceptions of Disability in American Life, n.d.; Blakemore, n.d.)

Poorhouses often exploited labor from those residents who could work. Poor farms were very similar to poorhouses, but were located in rural areas and inmates had to do farm labor. In many of these poorhouses and poorfarms, inmates were subjected to “often draconian control of what they ate and wore and how they worked and acted,” which in addition to being segregated from society, left very little freedom of any kind, not to mention reproductive freedoms (Blakemore, n.d.).

The legal structure of guardianship was also established in the colonial period of the United States, and often restricted reproductive freedoms of disabled people. The first guardianship law was established in the US in 1641. Guardianship gives another person or government legal control over someone’s decisions when they are deemed “incompetent” to make their own. Another form of guardianship was called a civil commitment, in which a state or local government acts as the guardian of an individual, who often was placed into a segregated facility such as a poorhouse (Guthrie et al., 1996). Disabled children under guardianship were often hidden away by parents, and prevented from romantic relationships or marriage. People of the time often viewed people with disabilities through the lens of “forever child syndrome,” which views disabled people as too immature to ever engage in a sexual or romantic relationship. Many people under guardianship were institutionalized, especially during puberty if they could get pregnant. For example, the Pennsylvania Institution for Childbearing Women was created with this purpose in mind(Kempton & Kahn, 1991).

In an attempt to improve the conditions for disabled people, during the revolutionary period, some thinkers designed segregated “special schools” that housed disabled children (Kempton & Kahn, 1991). The first of these was the Connecticut Asylum (at Hartford) for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons, which opened in 1817 (Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, 2014). While created with more progressive and educational intentions, these special schools often trained people to hide their disabilities, and had a very low tolerance for dexplays of romance or sexuality from students (Kempton & Kahn, 1991).

Image description: Grayscale image of a poorhouse that shows a crowded warehouse with a row of people sleeping on the floor, a row of people standing and working behind them, and two figures standing and talking in the balcony above.

Source: (Blakemore, n.d.)

Institutionalization

In the 1800s and picking up in 1880s with eugenics, people with disabilities began to be housed in separate, segregated institutions rather than in poorhouses with other minority groups. These institutions were created with the idea of providing better medical care to disabled people, however were often overcrowded, unsanitary environments where cruel treatment was common (Action for Access - Changing Perceptions of Disability in American Life, n.d.). They became a widespread phenomenon, and as many as 560,000 people were institutionalized by the 1950’s (Treatments for Mental Illness | American Experience | PBS, n.d.).

Residents in institutions were subject to restraint, had no access to sexual freedoms, and prevented from integrating into the community where socialization or relationships could occur. In the early 1900’s, people in institutions were especially at risk for forced sterilization(Action for Access - Changing Perceptions of Disability in American Life, n.d.). People in institutions were often punished for showing sexual or romantic behaviors, and received no sexual education. And unlike people in the outside world, people in institutions were unable to learn from peers and communities about sexual education or social conduct because they could not integrate into society, and therefore were often left with a lack of critical social skills and sexual health information (Graham Holmes & SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, 2021).

Image description: Black and white image of a room in an institution, where a large room is packed with white metal beds, and one person can be seen lying down alone in one of the beds.

Ugly laws

In a eugenic attempt to remove disabled people and minorities from society, beginning in 1867, local governments passed “ugly laws” to prevent those deemed “disgusting or improper” from going out in public. This stigmatizing law cast disabled people, poor people, racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, and LGBTQ+ people as ugly and disgusting people who were a harm to general society. Such people were often removed from the streets and incarcerated in jails, poorhouses, or institutions. This blocked disabled people from socializing in communities, building relationships, and exercising their rights to an integrated life in society. These ugly laws lasted for a very long time, with the final “ugly law” being repealed in Chicago in 1974, after an arrest that occurred earlier that very year (Marini et al., 2017).

Image description: Black and white image of two police officers arresting a man in a black suit and hat who is using crutches. The man with crutches has a surprised and sad expression on his face. There are buildings in the background since this takes place in Chicago in 1954.

Image source: (Greiwe, 2016)

Forced sterilization

In addition to restraint and segregation from society, the eugenic movement led to the creation of state laws preventing people with disabilities from reproducing. In 1896, the first state law made it illegal for disabled people to have sex or marry, or otherwise face 3 years in prison. Multiple other states followed suit and passed their own similar laws, and these laws eventually expanded into laws for forced sterilization (Marini et al., 2017). In 1907, the first state law was passed that allowed doctors in institutions to perform forced sterilization, a medical procedure without consent that takes away someone’s ability to have children. These laws multiplied across states, and by the 1970’s, over 60,000 people both inside and outside of institutions had been forcibly sterilized under 33 state laws (Eugenics, 2012). These procedures targeted multiple minority groups, and disabled, racial/ethnic minorities, low-income, and others were sterilized (Stern, 2020).

Forced sterilization laws became so widespread as to be upheld by the Supreme Court. In 1927, an institution in Virginia sought to sterilize Carrie Buck, the daughter of Emma Buck, both of whom were deemed “feebleminded” and who were put into the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded. This case was intended from the very beginning as a test case, so that forced sterilizations of people with disabilities could be approved across the United States. The case was pushed all the way to the Supreme Court, that stated forced sterilization of disabled people did not go against the Constitution, infamously stating that “three generations of imbeciles is enough.” This Supreme Court decision also removed parental rights from people with disabilities, which was used as precedent for the customary practice of removing custody and taking away children from parents with disabilities (Wolfe, 2022).

Forced sterilizations continued for decades afterward Buck vs. Bell, until the 1970’s when legal cases began to decide against their use. One of the most famous of such cases was Relf vs. Weinberger, when Alabama ended state funding of forced sterilization in 1974. However even after these cases, forced sterilizations is still performed, while on a more limited basis, in the modern day (Ko, 2016).

Image description: Black and white image of Emma and Carrie Bell, wearing white long work dresses and sitting on a bench with a farm field and trees in the background. They have neutral expressions on their faces and Emma is placing her arm on Carrie’s shoulder.

Image source: (Wolfe, 2022)

Deinstitutionalization

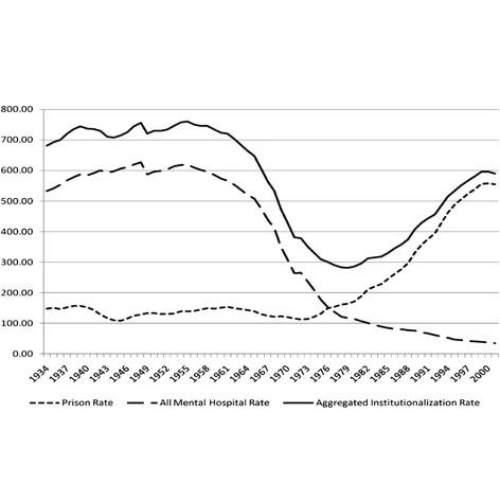

Starting in 1955, the deinstitutionalization movement was brought about by activists shining light on cruel institutional conditions, and the introduction of antipsychotic drugs that allowed patients to be treated while living in the community . While releasing disabled people from institutions marked a liberating step in the right direction, a significant lack of planning and support for the released individuals led to multiple problems with reintegration. The community supports providing necessary care in the community for the released residents were widely unavailable. Rather than facilitating a smooth transition to community life, “deinstitutionalization” looked more like a switch from mental hospitals to jails and prisons, as many of the released residents were reincarcerated through the justice system (Frazier et al., 2015; Torrey, 1997). The movement thus was not the liberating process that governments and the public had expected.

Additionally, having been segregated from society for so long, many freed residents lacked education on sexuality and social conduct and had a hard time adjusting to community life. The failures faced by the deinstitutionalization movement were one key factor in driving lawmakers to start thinking about the necessity of sexual education for people with disabilities (Graham Holmes & SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, 2021).

Image description: Black and white line graph that has two humps in it, the first hump taller than the second one, and shows the rate of institutionalization on the y axis and the year from on the x axis. The two humps show that after the first surge in incarceration by putting people with disabilities in institutions and mental hospitals, the Deinstitutionalization movement reduced briefly the number of incarcerated people, but then incarceration resurged as people were put into prisons and jails.

Image source: (Frazier et al., 2015)

Legislative steps towards access

In combination with all of the reproductive freedom restrictions mentioned so far, disabled parents routinely had their children taken away through legal custody cases, and were excluded from sexual health care and child services due to accessibility, stigma, and policy (Kempton & Kahn, 1991; National Council on Disability, 2019). The later half of the 1900’s became an important period of growth in access to reproductive freedoms and human rights for people with disabilities in general, as the disability rights movement picked up momentum from the civil rights movements of that era. These resulted in multiple laws to promote the rights of disabled citizens.

In 1973, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act prohibited discrimination against people with disabilites in programs that receive federal funding, thus advancing access for disabled people in needed reproductive and general health clinics, child support services, education, and many other areas (Powell, 2019). However, the original law was not widely implemented, sparking sit-ins from the disability community in 1977 to demand its implementation (Carmel, 2020). In 1979, the Supreme Court case re Marriage of Carney was one of the first widely-known cases to retain child custody with disabled parent. This case was critical to changing the widely-held societal view that disabled people are not fit to be parents or care for children (National Council on Disability, 2015).

In 1990, the first comprehensive civil rights law for people with disabilities was established in the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (McKeever, 2020). This law was based both on the Civil Rights Law of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act(Introduction to the ADA, n.d.). The ADA prohibits discrimination against disabled people in all areas of public life, and in all public and private areas that are open to the public. This law expanded meaningful access to work, services, and public life for disabled people and is the foundational law used today to protect the civil rights of people with disabilities (Powell, 2019; Silvers et al., 2016). In 1999, in light of the continuation of institutionalization, while on a smaller scale than in 1880-1950, the Olmstead Supreme Court decision stated that segregation in institutions violates the Constitution, sparking a greater push for accessible services within communities to serve disabled people outside of segregated institutions (Olmstead: Community Integration for Everyone -- About Us Page, n.d.).

Image description: During the Section 504 sit-ins in San Francisco, around 50 people with disabilities, most of them wheelchair users, sit in a circle around a single woman standing up and speaking into a microphone. The crowd fills up the entirety of the room and a man with a large video camera can be seen standing in the back.

Image source: (Trainer, 2017)

Beginning of disability-inclusive sexual education

Prior to 19th century, sex ed was widely not taught to disabled folks, and education in general was not distributed equitably to people with disabilities. The previously mentioned issues with the deinstitutionalization movement got lawmakers thinking about the importance of disability-inclusive sexual education, and in 1975 the Handicapped Children Act (now called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) was passed. This law mandated education for people with disabilities, and created a push for sexual education in this group as well. However, sex ed back then focused only on preventing pregnancy and risk rather than empowering choices, echoing the US history of eugenic beliefs that disabled people should not reproduce. In response to the state of civil rights for people with disabilities, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006 addressed the insufficiency of sexual education for disabled people, and stated that disabled people have right to same range and quality of sexual education as non-disabled people. Much work remains to be done, but this Convention provided a strong starting point to provide empowering disability-inclusive sexual education (Graham Holmes & SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, 2021).

Modern-day impacts

While much has changed and improved throughout history in the realm of sexual and reproductive freedoms for people with disabilities, it can be surprising how frequently echoes of history remain present today.

Unfortunately, forced sterilization still remains alive and well, while done to a lesser extent than in the past. People with cognitive and non-cognitive disabilities are more likely to be sterilized, and at younger ages, than nondisabled people (Li et al., 2018). Some states have even passed forced sterilization laws as recently as 2019 (National Women’s Law Center & Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network, 2021). Today, many cases of forced sterilization are often because of guardianship or incarceration (McKay, 2020; National Women’s Law Center & Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network, 2021). People of color and low-income people are also more likely to be sterilized without consent, especially those who are incarcerated or in immigrant detention facilities (McKay, 2020). It is important to know that forced sterilizations have never truly ended.

Marriage and sexuality are often difficult to access for disabled people even today. Institutions, while existing with much higher quality of care and freedoms, are still widely used. About 2 million disabled people were institutionalized (including corrective facilities) as of 2000 (She & Stapleton, 2006). Additionally, guardianships are still extremely common, and when technically not “allowed” to prohibit sex, guardians can prevent someone from going on dates or meeting people (Mamas & Resnick, 2017). People in guardianships are less likely to go on dates or to marry, and some guardianships take away an individual’s right to marry without the guardian’s consent (National Council on Disability, 2019). Additionally, insurance and legal issues can lead to a reduction in benefits for people with disabilities when married. For example, Social Security can be greatly reduced and disabled people can risk losing healthcare coverage if married, and if living together while unmarried, couples can be judged to be “holding out” and still face the penalty (Garbero, 2021). These barriers and multiple others still stand in the way of relationship and marriage freedom for disabled people today.

Parenting rights are also often at risk for people with disabilities in modern US society. Discrimination exists in custody cases and in adoption, and 40-80% of parents with intellectual/developmental disability have their children taken away (Reeves, 2013). In fact, 2/3 of dependency statutes say disability can be used to determine a parent is unfit to care for their child (“Parental Rights and Disabilities,” n.d.). This is a critical issue for reproductive rights in a country where over 4.1 million parents also have disabilities (Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation & National Council on Disability, 2016).

Finally, people with disabilities frequently encounter barriers to sexual health care and sexual education. In fact, 36 states fail to include youth with disabilities in their sex education requirements or provide resources pertaining to accessible sex education curriculum for youth with disabilities (Graham Holmes & SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, 2021). There exists a significant lack in accessible healthcare services for disabled people both in sexual health and general health. For example, there is discrimination in receiving reproductive-facilitating technology, and in receiving childcare services as a parent with disabilites (National Council on Disability, 2012; Reeves, 2013). Some barriers to such health services include inaccessible medical equipment, physician bias, financial inaccessibility, and clinic and legal policies (Matin et al., 2021; Powell, 2019; Silvers et al., 2016). Challenges to exercising reproductive freedoms are thus present in multiple aspects of a disabled person’s life.

Image description: A map of the United States on a light blue background has each state colored in as dark purple, light purple, or green. In the key below, gray text explains that dark purple means “forced sterilization is allowed;” green means “forced sterilization is banned,” and light purple means “It is not clear if forced sterilizations are allowed. Includes Puerto Rico, Guam, and Virgin Islands.” The states colored purple are: WA, OR, CA, NV, UT, ID, WY, CO, KS, AR, ND, MN, IA, IL, IN, KY, MI, ME, NH, VT, NY, PA, VA, SC, GA, HI, and FL. The states colored green are: NC and AK The states colored light purple are: MT, AZ, NM, SD, NE, OK, TX, MO, LA, WI, TN, MS, AL, OH, WV, and RI.

Image source: (National Women’s Law Center & Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network, 2021)

Conclusion

People with disabilities have faced centuries of restrictions to their sexual and reproductive freedoms, through multiple different ways including legal policies and societal stigma. Many of these barriers have basis in ableist and eugenics policies that believe that disability is a harm to society, ideas which have also been used to discriminate against other marginalized groups such as racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, LGBTQ+ people, and low-income people. Unfortunately, and while often without conscious intent, many of the historical barriers to reproductive freedoms have carried on to the modern day, while often in a different form. It is crucial that we understand the history of sexual and reproductive freedoms so that we can recognize their echoes today, and work for the empowerment of people with disabilities through education, access, and protection of legal rights.