Queer Disabled History: Activists & Events

By Maddie Fowler and Gracee Wallach, Disability-inclusive Sexual Health Network (DSHN)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Timeline

Events

Activists

Works cited

Submit article additions and edits

Introduction

November 22-December 22 is Disability History Month, when we remember the critical activists whose work laid the foundation for all we do today. One way the Disability-inclusive Sexual Health Network (DSHN) seeks to empower people with disabilities is through celebration of the rich overlap between the disability and queer communities. Throughout history, the disability and queer communities have shared powerful solidarity, although this overlap is often overlooked. Each identity of disabled LGBTQ+ activists influenced their work and created progress for social change, and it is important to honor them for all of who they were. Disability’s intersection with other identities is worth looking at more deeply, especially when disabling conditions can result from sexuality-, gender-, class-, and race-based discrimination and oppression in health care and access, stable and safe housing, and many other areas.

Queer and disabled people are everywhere, and have always been here, whether recorded in history or not. This article uplifts the important intersection of the disability and LGBTQ+ liberation movements through a compiled list of events and activists within the realm of gender, sexuality, and disability advocacy. While this post focuses on the shared space between disability and queerness, rich intersectionality with movements for racial and ethnic equality, immigrant justice, and other movements was also present within disability rights efforts, and is shown through many of the events and activists’ work. This article cannot and does not provide an exhaustive list of activists and events within the LGBTQ+ and disability rights movements, both due to their sheer number, and the fact that many have been erased by white supremacist, ableist, homophobic, and transphobic efforts. Oppressive cultures erase marginalized identities to shape narratives of the past in their own favor. This erasure makes it even more important to recognize and honor marginalized ancestries in order to empower individuals today. This article contains a submission form where readers are invited to enter suggestions for activists and events that are not represented here, so we may actively bring visibility to overlooked history.

Events

People mentioned who are detailed in the Activists section have an asterisk next to their name.

1848: Seneca Falls Convention

Image description: To celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Seneca Falls convention, a group of about 40 people gather in Seneca Falls, New York. The people in the crowd are sitting and standing and most are looking at the camera. Behind them is a brick wall with windows that displays two US flags and one US flag pleated fan bunting centered above them. [1]

On July 19-20, 1848, the first recorded US Women’s Rights Convention took place in the Wesleyan Chapel of Seneca Falls, New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the four other organizers of the convention were active suffragists and abolitionists. Many of the queer disabled activists during this time period were also suffragists (advocates for the right to vote). The Declaration of Sentiments was presented at the Seneca Falls Convention as a document modeled after the Declaration of Independence that expressed the values and goals of women’s rights. [2] Although this Convention was critical to the women’s rights movement, it was centrally concerned with freedoms for white, non-disabled, middle- and upper-class, educated, propertied women. No Black women attended the convention, and many suffragists even felt that an approach inclusive of women and people of color inclusive would get in the way of their movement's success. Some suffragist ideals during this time were also based in ableist ideology that only nondisabled people were deserving of the vote, and thus women deserved the vote because the majority were nondisabled. [3]

1868: 14th Amendment ratified

On July 9th, the 14th Amendment granted “equal protection of the laws” to all those born or naturalized in the United States. This amendment provided citizenship for formerly enslaved African Americans after abolition and has since been cited as Constitutional backing for many civil and equal rights movements. [4]

1880: National Association of the Deaf’s first convention

Holding its first convention on August 25, 1880, the National Association of the Deaf is the oldest civil rights organization in the entirety of the United States. NAD is an organization by and for Deaf people that has supported many of the disability rights laws in place today. [73]

1882: First legal case against LGBTQ+ discrimination

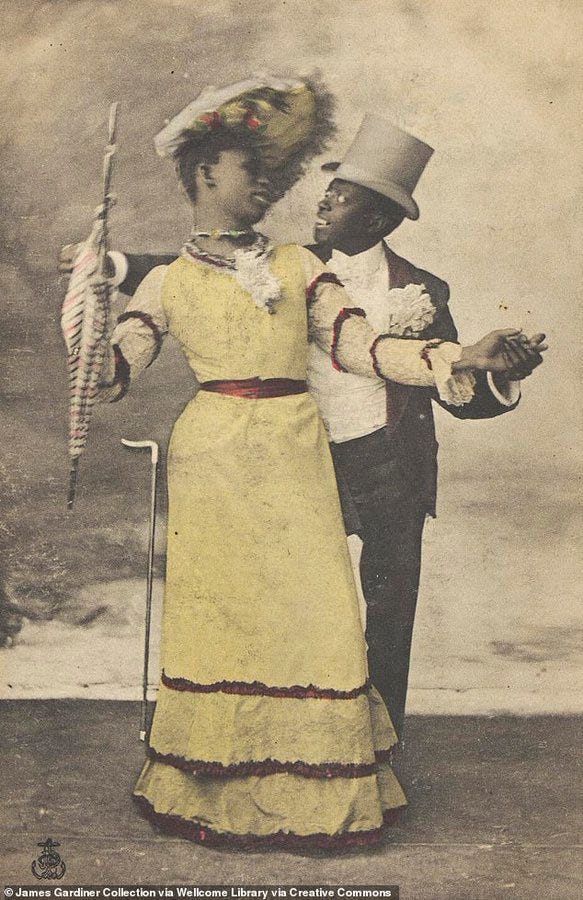

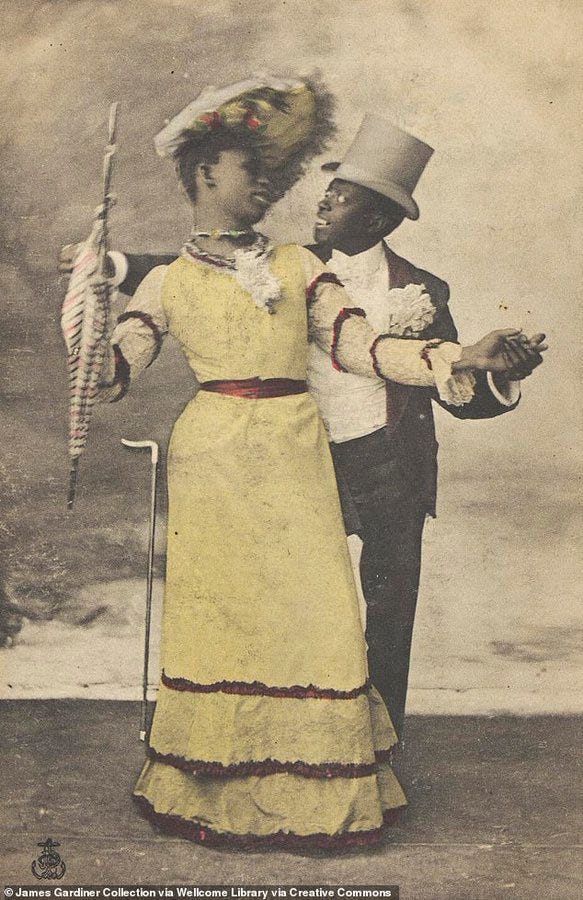

Image description: Two Black actors, one in drag, circa 1903. One actor wears a suit and gray top hat while the other actor wears a long yellow dress with red trim and a wide-brimmed feather hat, and holds a folded umbrella. The actor in drag stands in front and rests their hands upon those of the other actor, as both gaze smilingly into each other’s eyes.

William Dorsey Swann*, in response to charges for hosting drag queen parties, files for a presidential pardon but is denied. This case marks the first recorded legal action against discrimination towards a group of queer people. [5]

1920: 19th Amendment ratified

Image description: Alice Paul from the National Woman's Party stands on a balcony and unrolls the ratification banner with its new 36th star into a crowd of cheering women standing on the cobbled street below. The banner is a long striped cloth covered with two rows of stars. On either side of the balcony, US flags hang next to windows with flower beds. [6]

On August 18th, 1920, the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote as citizens of the United States. Many of the queer disabled activists during this time period were also suffragists. [7] Unfortunately, while this and the 15th amendment should have allowed Black men and women the full right and ability to vote, most were effectively barred from voting until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1924: The Society for Human Rights formed

While stationed with the U.S. army in Germany, Henry Gerber witnessed the rise of homophile organizations (historical term for gay rights groups) and was inspired by the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, an organization against Germany’s homophobic laws. He began the Society for Human Rights in Chicago in December 1924, the first gay rights organization in America. They produced the first ever gay rights newsletter in the US, called “Freedom and Friendship.” Shortly after the newsletter was released, police arrested Gerber, raided his home, and took his papers, so Gerber lost his job and life savings – and the Society for Human Rights was dismantled.[8]

1932: Franklin D. Roosevelt becomes first US president with a disability

FDR contracted polio in 1921 and was paralyzed from the waist down. He went on to become the first person with a disability to be elected president in 1932. During his time as president he supported the founding of the March of Dimes and now has his likeness on the US dime coin. [72] This charity work for disability, however, contributed to harmful images of disabled people by portraying them as pitiable and defenseless, images that persist in society today.

1935: Social Security Act

FDR signs the Social Security Act into law to establish a permanent form of support for adults with disabilities. [72]

1940: National Federation of the Blind

The National Federation of the Blind was founded on November 16, 1940 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The NFB is an organization by and for Blind people that seeks to "promote the economic and social welfare of the blind" and change public policy for disability rights. [74]

1950: The Mattachine Society formed

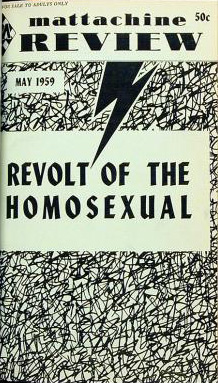

Image description: On cover of Mattachine Review, the title “Revolt of the Homosexual” is printed in bold black font on fading green and tan paper. The page is covered in black squiggles, with a black lightning bolt piercing through the top of the page. Beside the journal name comes the price “50¢”, and below the name the date “May 1959” is written in small font.

Harry Hay founded The Mattachine Society in the early 1950s, which provided a safe space for gays and lesbians to discuss and share their experiences together. The Mattachine Society declared that gays were an oppressed minority and community was essential to confront their oppression. However, in 1953, they adopted an accomodationalist approach, saying that gays should assimilate to heterosexual lifestyles to achieve equality. The organization’s efficacy after their change in ideology is widely argued today, some saying it flourished and achieved policy changes, and some saying that membership dwindled. The Mattachines dissolved in the late 1960s, when gay rights activism surged in the US. [8]

1954: Brown vs. Board of Education

School segregation based on race is abolished; and in a lesser-known advancement, this case gives public schools permission to educate people with significant intellectual disabilities. [72]

1955: The Daughters of Bilitis formed

Image description: Six members of the Daughters of Bilitis gather around a table, all of them laughing and smiling. The table is loaded with plates of food, mugs, and tableware. Del Martin sits at the far left; Phyllis Lyon sits at the far right.

The Daughters of Bilitis was founded by Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin in 1955 in San Francisco, and spread across the US and into Australia. They provided a meeting place for lesbians, held public forums about homosexuality, provided support to lesbians and lesbian mothers, and promoted lesbian feminist politics. The group dismantled in the early 1970s, but set a critical precedent fostering understanding of the lesbian community. [8]

1958: First Supreme Court ruling in favor of gay rights

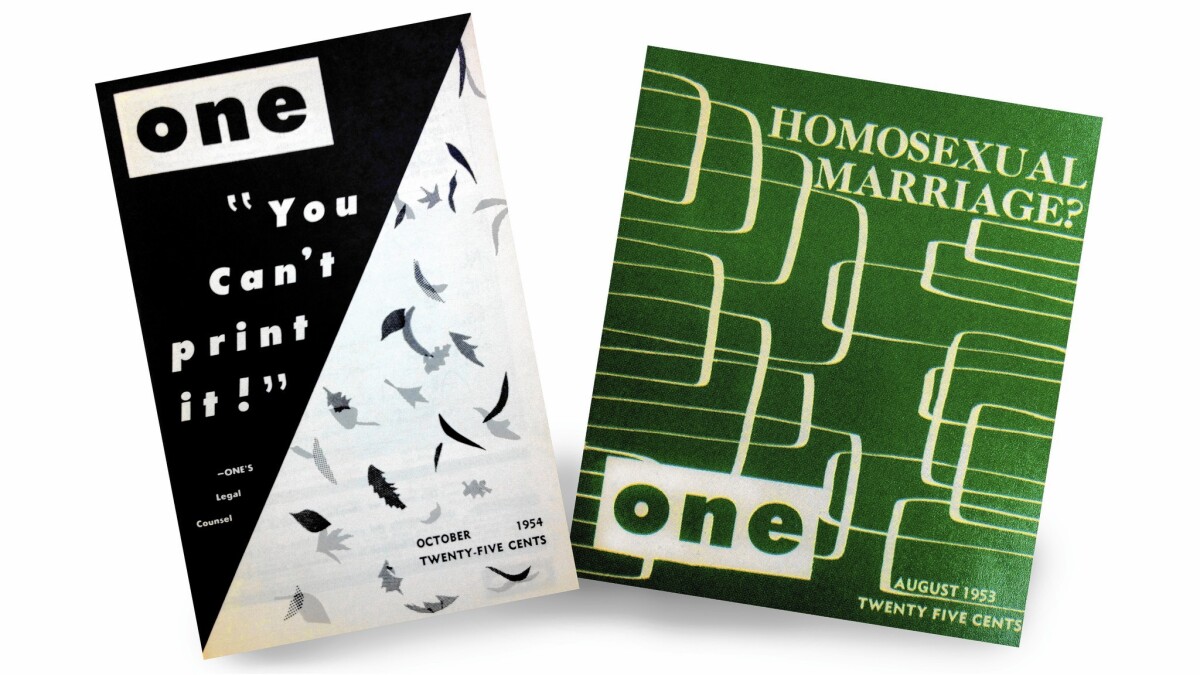

Image description: Two issues of ONE: The Homosexual Magazine are pictured positioned side by side. The issue on the left shows the name “One” with the words, “You can’t print it!” written in a black triangle that covers the top left half of the page. Under the black triangle is a white triangle filling the second half of the page, depicting grayscale falling leaves and the words “October 1954, Twenty-five cents.” The issue on the right has a green color covered in white geometrical curving lines, with the title “Homosexual Marriage” at the top. On the bottom of the page is the name “One” with the words “August 1953, Twenty-five cents.”

After the U.S. Post Office refused to deliver America’s first widely distributed pro-gay publication, ONE: The Homosexual Magazine, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court (ONE Inc. v. Olesen). In January 1958, the Court ruled in favor of Oleson and in favor of gay rights for the first time in US history. [9, 10]

1962: Ed Roberts fights for access at Berkeley and begins Independent Living Movement

Ed Roberts, who was quadriplegic due to polio, applied to Berkeley and fought back when his admission was denied. During some of his university career a Berkeley, he was living in a hospital and denied many of the freedoms of college students. In response, he began the first Center for Independent Living (CIL) with federal funding. Today, the CIL has centers across the country and works for disabled people to live integrated lives in the community with the resources they need. [72, 76]

1963: President Kennedy sparks national support for deinstitutionalization

President Kennedy brings national attention and efforts to release disabled people from segregated institutions and allow them to integrate into community life through stronger community health programs. [75]

1964: Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed

US President Lyndon B. Johnson congratulates Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his office after the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. President Johnson sits at his desk and turns to extend his hands to Dr. King, who smiles approvingly at the president. Multiple men stand behind them and watch their exchange. [11]

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Public Law 88-352; 78 Stat. 241), outlawed racial segregation in public places and probited employment discrimination on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” [12]

1965: Medicaid

The Social Security Act was amended to provide funding for medical care for people with disabilities and for low income families. [72]

1965: Voting Rights Act passed

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was created to enforce the 15th amendment, but was not signed into law until 95 years after the amendment was ratified. The Act addressed the tremendous disenfranchisement of Black citizens through poll taxes, literacy tests, harassment, intimidation, and physical violence. As a result, very few African Americans were registered to vote, and they held little political power in their communities and across the nation. [13] Current policies and practices like gerrymandering, voter registration restrictions, lack of polling access, and more continue to prevent Black, Indigenous, Latinx, disabled, and poor Americans from voting.

1966: Gay rights “Sip-In”

Image description: Seven men in formal suits sit at a bar, all but one of them looking towards the bartender, who holds his hand over the top of a glass and talks angrily to the men at the bar. Under the bartop, shiny crystal glasses are aligned neatly, and behind the bartop chandeliers hang in the background.

When most establishments refused to serve gay people, the Mattachine Society staged a “Sip-in” on April 21st, 1966. They entered a bar in NYC, declared they were gay, and demanded to be served. [9, 14, 15]

1966: Compton’s Cafeteria Riot

Image description: A shiny gray stone is engraved in black with the words, “Gene Compton’s Cafeteria Riot 1966: Here marks the site of Gene Compton’s cafeteria where a riot took place one August night when transgender women and gay men stood up for their rights and fought against police brutality, poverty, oppression and discrimination in the Tenderloin. We, the transgender, gay, lesbian and bisexual community, are dedicating this plaque to the heroes of our civil rights movement. Dedicated June 22, 2006”

In August 1966, a riot broke out in Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco, after a policeman attempted to arrest a drag queen and she threw a cup of coffee in his face. Cops had been arresting drag queens, gay hustlers, and transgender women at the cafeteria regularly for cross-dressing, obstructing the sidewalk, or any reason they could find. After the incident, Compton’s banned trans women and the community protested by picketing and breaking its windows. The Compton’s riot received no media coverage in San Francisco, but is important as one of the first queer uprisings against police brutality in the US. [8]

1968: Architectural Barriers Act of 1968

In an effort to boost employment, the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 was signed into law to require all buildings designed, constructed, altered, or leased using federal funds to be accessible. Many of these standards were developed by disabled veterans and other people with disabilities who started the barrier-free movement in the 1950s. [72]

1969: The Stonewall riots spark the beginning of the LGBT movement and the Gay Liberation Front

Image description: A crowd of people in a bar are seen looking in different directions and talking or shouting, and a policeman with two other people face away from the camera while pushing into the crowd.

In the early morning of June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a New York City gay bar. The event led to a violent protest and a days-long series of riots that became known as the start of the LGBTQ civil rights movement in the US.

Immdiately after Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was formed, who organized a march to continue the momentum of the uprising. The GLF was composed of multiple groups and had a broad platform that included anti-capitalism, questioning gender roles and the nuclear family, denouncing racism, working with the Black Panther Party, and supporting international struggles. [9, 16, 17]

1970: Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) formed

Image description: Five people pose in an old black and white photo, Sylvia Rivera sitting on the floor in the center, two on their knees and embracing on the right, one leaning in with their hand on their hip on the left, and one shirtless and standing in the back. A group of people standing can be seen further behind them in the room. Underneath the photo are two black stars with text between them reading, “Photo e. Bedoz. S.T.A.R. Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries.”

Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, was organized by queer historical icons and drag queens Marsha P. Johnson* and Sylvia Rivera. Both were present at the Stonewall riots, and were active in GLF, and the Drag Queen Caucus. They created STAR to serve and empower homeless trans youth, drag queens, sex workers, immigrants, and low-income people. Rivera and Johnson were homeless themselves, and knew the people at STAR as their own children. They bought and repaired a building to provide shelter and clothes. STAR grew across the United States and into England and was active for about 3 years. [8]

1970: Judy Heumann launches her activism

After being denied a teaching license when her wheelchair was deemed a “fire hazard,” Judy Heumann sues the state of New York and launches her career of revolutionary disability activism. She worked with Ed Roberts to launch the Independent Living Movement and went on to work in the Clinton Administration as Assistant Secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services. [72]

1973: Roe v. Wade

Image description: Black and white photo of a crowd of people, many of them women, march down a street carrying protest signs and banners. A banner in the center of the photo reads, “Safe legal abortions for all women.” A smaller banner in the background reads “Stop the attacks on poor and working women! - Equal Rights Now.”

On January 22nd, 1973, the US Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide.[18]

1973: Homosexuality removed from the DSM

LGBTQ+ activists held demonstrations and presented at the May, 1973, American Psychiatric Association (APA) to speak against the pathologization of queerness in the Diagnostic and Statistucal Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), leading the APA to remove homosexuality from the DSM that year. [78] Since then, the conflation of queerness and mental illness and disability in the DSM has reduced, including the 2013 replacing of “Gender Identity Disorder” with “Gender Dysphoria.” However, “Gender Dysphoria” and “Transvestic Disorder” remain in the current day DSM, which pathologize trans people. [79]

1973: Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act passed

Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act was the first disability civil rights law in the US, and outlawed discrimination against people with disabilities in programs that received federal funding. While the law lacked teeth for implementation, it provided key foundations for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other disability civil rights laws. [19]

1974: Last “ugly law” repealed

Chicago repeals the last of the nation’s “ugly laws,” laws that banned so-called “diseased, maimed, mutilated” people from appearing in public. These laws attempted to segrate disabled and poor people from society entirely, and are similar to some of the laws that prohibited transgender people from dressing and presenting as they desired in public. [72, 77]

1974: Inaugural convention of People First

In October 1974, over 500 people attended the first Convention of People First in Portland, Oregon. People First is an organization of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities who got together to speak for themselves and promote their rights. [72,80]

1975: UN Declaration on the Rights of People with Disabilities

The United Nations presents a declaration including a preamble and thirteen proclamations that broadly proclaim the rights of people with disabilities. The Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities was adopted in 2007. [72]

1977: Section 504 sit-ins

Image description: During the Section 504 sit-ins in San Francisco, around 50 people with disabilities, most of them wheelchair users, sit in a circle around a single woman standing up and speaking into a microphone. The crowd fills up the entirety of the room and a man with a large video camera can be seen standing in the back. [20]

In protest of the lack of implementation of protections from Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, people with disabilities formed coalitions and joined together to form a response. They staged sit-ins, some of them days long, in government offices across the country to demand more effective implementation of Section 504. Other groups such as the Black Panthers supported these efforts through delivering meals to the occupied offices and other forms of solidarity. [21]

1977: Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf's first national conference

Image description: A newspaper headline on yellowed paper reads, “Upfront. December 7, 1979. The Rainbow Society of the Deaf Houston Chapter by Sybil Liberman.” Below the heading text is a short news story next to a black and white image of about 24 people who sit and stand in front of a table and smile at the camera while holding up the “I love you” sign in American Sign Language. The image is captioned with text above it reading, “The newly formed Astro Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf meeting at the home of new president, Bruce Herman.”

Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf (RAD) is an organization promoting the rights and offering community and opportunities for Deaf and hard-of-hearing gays and lesbians. It was founded and held its first national conference 1977 in Fort Lauderdale, FL. RAD today has more than twenty chapters across North America, and continues to hold a biennial national conference. [22]

1978: Americans with Disabilities for Accessible Transportation (ADAPT)

Nineteen people who would go on to form ADAPT stage their first joint protest against inaccessible transportation in Denver, CO by blocking buses with their wheelchairs. The group when on to officially found ADAPT in 1983, and engaged in many more demonstrations, including the Capitol Crawl that led to the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. They have since changed focus to communities and attendant services and renamed themselves, American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today. [72]

1979: US implements key protections from forced sterilization

On March 8, 1979, the US implemented regulations prohibiting federally funded providers from performing forced sterilizations on people under age 21.[70] One key case leading to this decision was Stump v. Sparkman, in which a mother decided to have her daughter with intellectual disability forcibly sterilized without her consent. [71] However, forced sterilizations of people with disabilities, people of color, and immigrants has continued across the US and globally through today.

1980: Womyn’s Braille Press founded

Womyn’s Braille Press was founded to make lesbian and feminist literature accessible to people with vision impairments. They have produced and circulated over 800 books on tape and 40 in Braille, along with a quarterly newsletter distributed in print, in Braille, and on tape. These initiatives created a sense of community among disabled lesbians and other women. [22]

1981: First Disabled Lesbian Conference

Activist Connie Panzarino* organized the first Disabled Lesbian Conference following the Michigan Women’s Music Festival. [22]

1983: Dykes, Disability & Stuff (DD&S) grassroots newsletter began

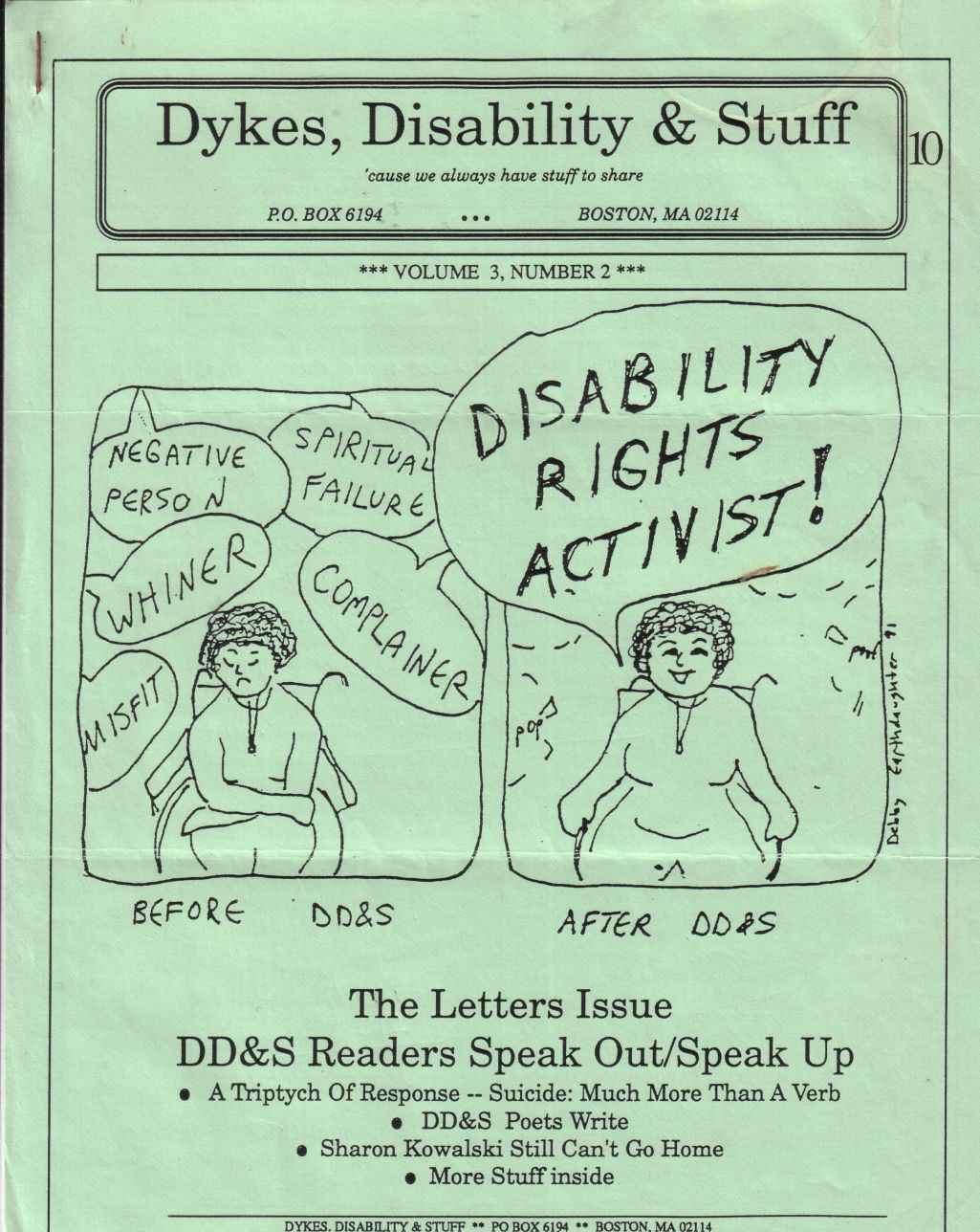

Image description: The newsletter entitled “Dykes, Disability & Stuff” is printed on green paper. Underneath the title, text reads “Cause we always have stuff to share. P.O. Box 6194...Boston, MA 02114. Volume 3, Number 2.” In the middle of the page is a two panel cartoon of a person sitting in a wheelchair. The first panel is captioned “Before DD&S” and shows the person looking sad and crossing their arms while surrounded by speech bubbles reading, “Negative person, Spiritual failure, whiner, complainer, misfit.” In the second panel, captioned “After DD&S,” the person looks happy and has their arms resting on the wheelchair armrests while saying, “Disability Rights Activist!” Underneath the cartoon, text reads, “The Letters Issue: DD&S Readers Speak Out/Speak Up. A triptych of response-- Suicide: Much more than a verb. DD&S poets write. Sharon Kowalski still can’t go home. More stuff inside.”

Dykes, Disability, & Stuff is a Wisconsin-based quarterly grassroots newsletter featuring news, reviews, literature, and art, and is available in standard print, large print, audio cassette, Braille, DOS diskette and modem transfer. DD&S actively promotes access to lesbian culture and community. [22]

1988: Deaf President Now! at Gallaudet University

At the world’s only university designed for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, students took a stand to demand the school’s first Deaf president since its founding in 1864. [72]

1989: Ring of Fire: A Zine of Lesbian Sexuality founded

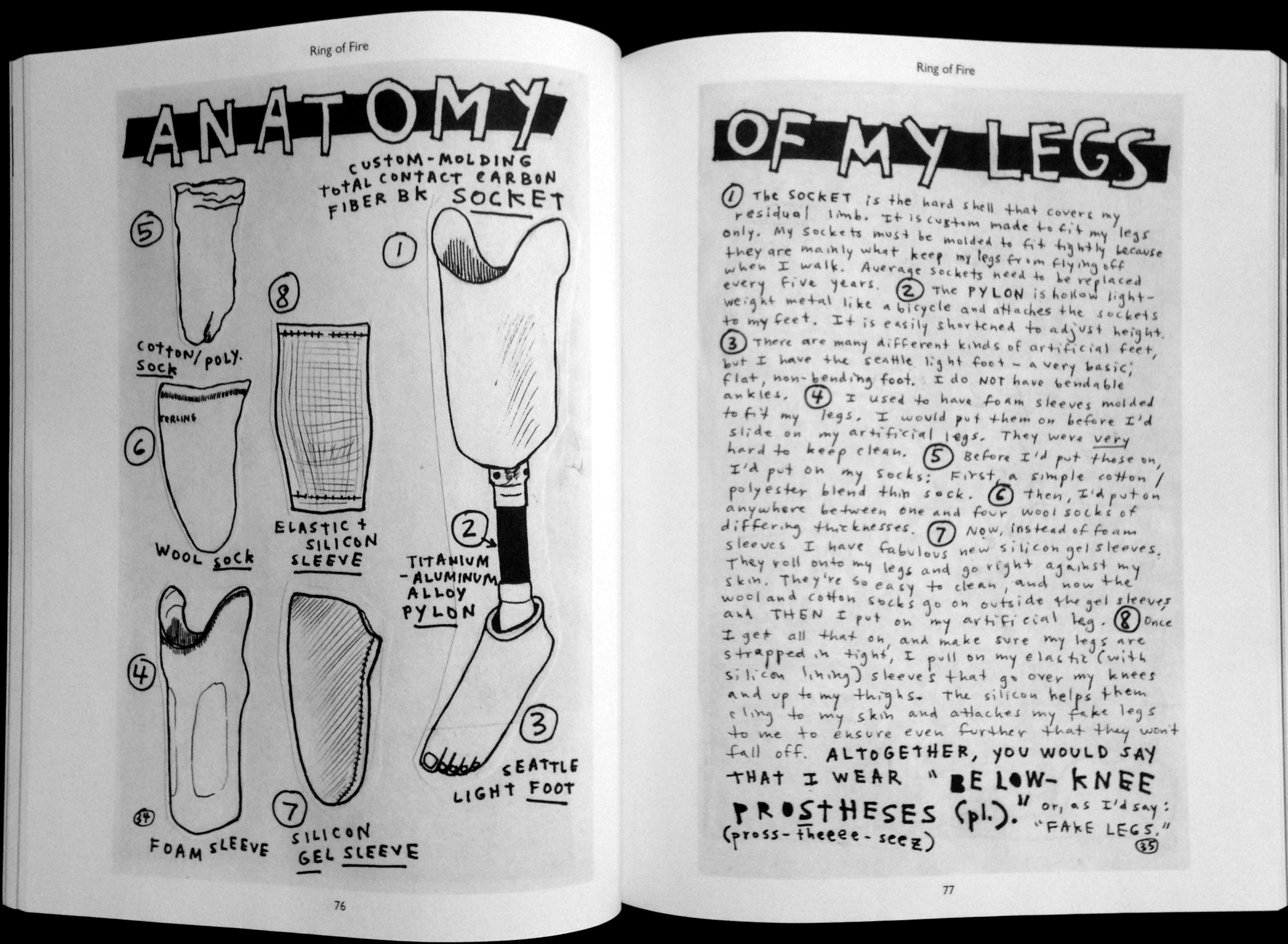

Image description: In the publication Ring of Fire, two handwritten pages are scanned and shown on sequential pages. The title “Anatomy of My Legs” is written in block letters with a black background across the top of the two scans. On the left page, a model of a below-the-knee prosthesis is sketched and its parts are separately numbered and labeled. On the right page, numbers corresponding to the prosthesis parts are followed by more detail.

Ring of Fire: A Zine of Lesbian Sexuality was founded by Hillary Russian, a young disabled dyke in Seattle, Washington. The publication prints regularly and offers erotic and humorous stories about gender-bending, crip culture, living with a disability, and sex. [22]

1990: Capitol Crawl

Image description: Dozens of people climb up the steps to the US Capitol in a black and white photograph, with the white peaked dome of the Capitol building visible at the top of the image. [23]

On March 13th, 1990, ADAPT staged a march and protest of over a thousand people with disabilities and allies at the U.S. Capitol to urge the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Hundreds of wheelchair users abandoned their wheelchairs and crawled their way up the Capitol steps, making visibly apparent the necessity for accessibility and equal protections for people with disabilities in the U.S. [24]

1990: Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Image description: President George H.W. Bush signs the Americans with Disabilities Act in the South White House lawn. He sits at a desk with two people on either side of him (two in wheelchairs, two standing up behind them). The background contains a bright green lawn and light blue fountain, with a blurry crowd shown in the distance. [25]

In the first civil rights act entirely dedicated to people with disabilities, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law by President George Bush on July 26th, 1990. The ADA prohibits discrimination based on disability in community life and employment and requires “reasonable accommodations” to allow accessibility of most public and private spaces for people with disabilities. [26, 27]

1990: First Disability Pride Parade

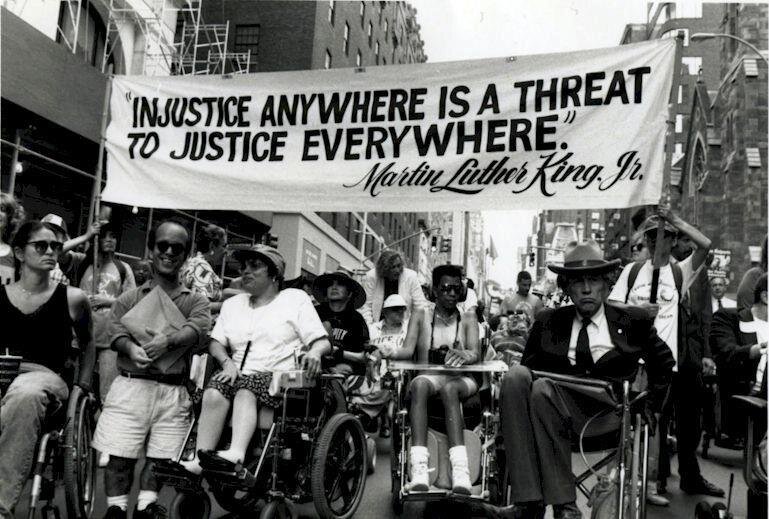

Image description: A crowd of protestors led by 6 wheelchair users in the front row rolls down the NYC streets, with tall buildings on either side. In the second row of the procession, two people hold a white sign that reads, “‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ -Martin Luther King, Jr.” [28]

To mark the passing of the ADA, disabled people in Boston hosted the first-ever Disability Pride Day featuring speakers and the first Disability Pride Parade. Disability Pride celebrates disability as a part of human diversity, similarly to how LGBTQ+ Pride provides space to celebrate queerness. Disability Pride parades have continued to this day across the US and the globe. [29]

1992: Deaf Gay and Lesbian Center formed

The Deaf Gay and Lesbian Center (DGLC) was formed to serve Deaf and hard-of hearing LGBT communities in San Francisco through advocacy, empowerment, and communication access. [22]

1997: Deaf Youth Rainbow

Deaf Youth Rainbow was launched under the Capital Metropolitan Rainbow Alliances in Washington, D.C., to provide a safe, supportive educational space for Deaf and hard-of hearing youth. [22]

1999: Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W.

States are required to provide services for people with disabilities in the community rather than in segregated institutions, reinforcing the right of disabled people to live integrated with the rest of society. [72]

2000: Vermont is the first state to legalize same-sex marriage

Image description: Seven people, gather in a green lawn in front of a city informational signpost and smile at the camera. Five of the people have gray hair, two of them wear rainbow tye-dyed t-shirts reading “It’s just love,” and one of them uses a cane. The signpost behind them is green with white text entitled “Vermont equality for same-sex couples.” More white text is under the title but too small to read. Three more people and a forest of green trees are in the background.

In April, 2000, Vermont became the first state in the US to give same-sex couples the right to civil unions — legal partnerships that grant the same rights and benefits as legal marriages. [9, 30]

2002: Sharon Duchesneau and Candy McCullough have a Deaf child

Image description: Sharon Duchesneau and Candy McCullough hold hands while embracing their child, who wears a graduation cap with a purple tassel. In the background is a large brick building with white columns.

Sharon Duchesneau and Candy McCullough, a Deaf lesbian couple in Bethesda, Maryland, announced their decision to select a Deaf sperm donor to increase the liklihood their child would be Deaf. A Washington Post Magazine article about the couple sparked a national debate about their choices. While many recognized the couple’s lesbian pride, many more were highly critical of their decision to have a Deaf child. [22]

2002: First-ever Queer Disability Conference in San Francisco

Over 300 people attended the first-ever Queer Disability Conference in San Francisco, where topics included medical discrimination, coming out at work, queer crip performance, partners and allies, queer crip sexualities, and more. The conference offered space for discussions, community, networking, and mutual learning across a wide diversity of identities. [22]

2009: The Matthew Shepard & James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act becomes a law

Image description: While standing at a podium in front of a crowd, President Barack Obama applauds the sisters of James Byrd, Jr., Betty Byrd Boatner, second from right, and Louvon Harris, second from left, and the parents of Matthew Shepard, Judy Shepard, center, and Dennis Shepard left, after signing the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

In October 2009, President Obama signed the act that was named for two men who were murdered in hate crimes. Matthew Shepard was murdered because he was gay, and James Byrd, Jr. because he was Black. The law expanded previous legislation to officially categorize crimes motivated by actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability as hate crimes. [9, 31]

2015: Obama calls for end to conversion therapy

Image description: Five people holding rainbow flags and protest signs stand in a road with buildings and a mountain in the background. The protest signs read, “Self hatred is not therapy, Homophobia has a cure: education, and Love needs no cure.”

After the tragic suicide of a transgender teenager who was subjected to Christian conversion therapy, in April 2015 President Obama publicly called for an end to the dangerous practice meant to change people's sexual orientation or gender identity. [9, 32] Unfortunately, it was not a full ban on conversation therapy. This influential moment inspired many autistic individuals to reassert their stances on the unjust legality, acceptance, and promotion of Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), a behavioral therapy for autistic youth that is founded by the same person who founded conversion therapy, Ivar Lovaas. [33]

2015: Supreme decision legalizes marriage between couples of any gender across the U.S.

Image description: Jim Obergefell and John Arthur hold hands on a plane while facing each other, with another person behind them. All three are smiling. John Arthur props up his legs and a medical pole sits next to him.

On June 26th, 2015, the Supreme Court decision in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, stated that couples of any gender can get married in all 50 states and be granted the right to full, equal recognition under the law. Many people called this landmark moment "marriage equality" – however, disabled people still face significant barriers to getting married as they cannot both get married and continue receiving the governmental and healthcare benefits necessary to survive. [34] What is also under-discussed is the actual couple whose denied rights were at the center of this case. Jim Obergefell and John Arthur were together for 22 years until John's death from ALS in 2013, only a few months after the two wed. They boarded a medically-equipped plane from Ohio, where same-sex marriage was not legal, to Maryland, where it was, and got married on the tarmac because of John's health conditions. When they returned home, the state of Ohio would not list Jim on John’s death certificate as his surviving spouse. James Obergefell went on to be a plaintiff in the fight for federal recognition of their marriage. [9, 35]

2021: US issues “X” gender marker option on passport

Image description: Dana Zzyym sits on a porch in front of a tree and looks off to the left. They wear a brown leather jacket, glasses, and have short hair that is half blonde and half red. They hold a cane with a rainbow ribbon on the handle.

In October 2021, the US issues its first passport with an X gender marker to Dana Zzyym, a disabled intersex veteran who had been fighting for an accurate gender marker in court since 2015. [36, 37]

Activists

Frances Thompson (1840-1877) [cancer and physical disability]

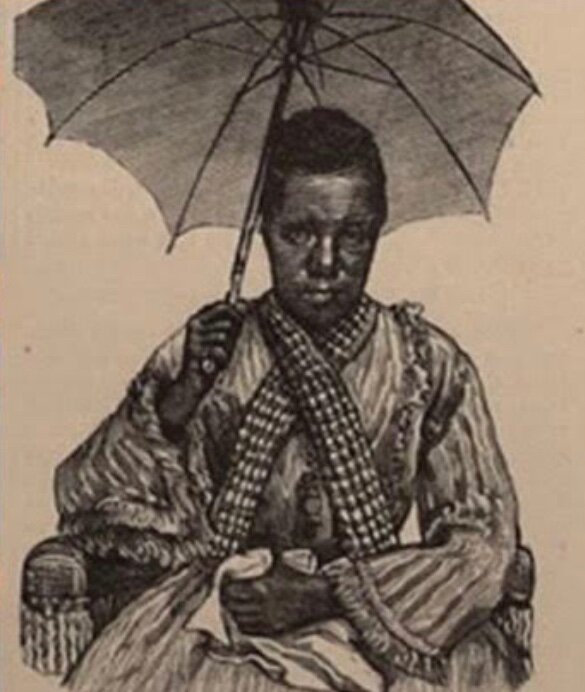

Image description: Frances Thompson is depicted in the only known representation of her. It is a black and white etched drawing on yellowing paper. She sits in a tasseled chair wearing a long sleeved dress and scarf and holding an open umbrella above her head. [38]

“I am woman.”

Frances Thompson was a trans woman and activist who was born into slavery and walked with crutches due to cancer in her foot. While living as a free woman during the Memphis Riots of 1866, she and her roommate were beaten and raped by white men and police officers. Afterwards, she became the first recorded trans woman in the US to testify before a congressional committee as she spoke out about the Memphis Riots. Ten years later, she was arrested and sentenced to work on a chain gang, and fell ill and died shortly after her release. Many documents containing information about her life were destroyed by state and government efforts, yet her activism and story living openly as a woman for nearly all her life is a critical piece of queer ancestry. [39, 40]

William Dorsey Swann (1858-1925) [heart condition]

Image description: Two Black actors, one in drag, circa 1903. One actor wears a suit and gray top hat while the other actor wears a long yellow dress with red trim and a wide-brimmed feather hat, and holds a folded umbrella. The actor in drag stands in front and rests their hands upon those of the other actor, as both gaze smilingly into each other’s eyes.

William Dorsey Swann was the first recorded drag queen and earliest known queer activist in the United States. He was born into slavery a few years before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. [41] As a free man, he hosted and attended drag balls for other formerly enslaved folks in Washington, DC, forming the earliest known US LGBTQ+ resistance group. [42] Swann was tried in court for these activities and advocated for a presidential pardon, making him the first person documented in the US to take legal action against the systemic oppression of queer people. During one of his trials, Swann’s doctor diagnosed him with a heart condition noting that imprisonment could endanger his life, but this plea was ignored. No photos of Swann remain and he is known today primarily through court documents, revealing figments of a rich queer history that has been largely erased by white supremacist and homophobic efforts. [5]

Jane Addams (1860–1935) [TB and physical disability]

Image description: Jane Addams is depicted sitting at a table in a sepia portrait and looks straight-faced at the camera. She rests an elbow on the table with an open book laying in front of her.

“I do not believe that women are better than men. We have not wrecked railroads, nor corrupted legislatures, nor done many unholy things that men have done; but then we just remember that we have not had the chance.”

Jane Addams was a famous lesbian suffragist and social worker for children and immigrants. She lived with curvature of her spine and chronic pain, and she used a back brace for much of her life. She founded the Hull House with her partner Elen Gates Starr, which served as a refuge for neglected and abused children and immigrants. She was a leader of women’s and pacifist movements such as the Women’s Peace Party, and was a co-founder of the ACLU and NAACP. In 1931, she won the Nobel Peace Prize. [43, 44, 45]

Edith Cooper (1862–1913) [rheumatism]

Image description: Edith Cooper and her partner Katharine Bradley are shown in a black and white portrait looking to the left of the frame with straight faces. They are standing close to each other with their faces almost touching, and wearing dark colored clothing. [46]

The world was on us, pressing sore;

My love and I took hands and swore,

Against the world, to be

Poets and lovers evermore.

[47]

Edith Cooper was a lesbian author who wrote with her partner, Katharine Bradley, under the shared pseudonym of Michael Field. She lived for over 40 years with Katharine, who was her primary caretaker when she developed rheumatism. Their over 40 works were critically acclaimed during their lifetime until the true identities behind their pen name were revealed. [46]

Edith Craig (1869–1947) [arthritis]

Image description: Edith Craig is pictured in a black and white portrait holding papers and wearing a sash reading “votes for women.” She has short wavy hair and looks straight faced off the left side of the frame.

“[I] grew up quite firmly certain that no self-respecting woman could be other than a suffragist.”

Edith Craig was a lesbian theatre director, producer, actress, costume designer, and suffragist. She lived with arthritis which interfered with her original plans of becoming a musician. She founded the Pioneer Players theatre society, and performed and produced historically banned productions featuring themes of feminism and women’s suffrage. [46]

Eva Gore-Booth (1870–1926) [TB]

Image description: Eva Gore-Booth is pictured with her sister, Constance, in a black and white portrait looking to the left of the frame with straight faces. They are standing close to each other with their faces almost touching and are wearing white draped clothing.

“There is a vista before us of a Spiritual progress which far transcends all political matters. It is the abolition of the ‘manly’ and the ‘womanly.’ Will you not help to sweep them into the museum of antiques?” [48]

Eva Gore-Booth was an Irish lesbian poet, dramatist, suffragist and activist, who was mentored by W.B. Yeats and emphasized the role of women in her writing. After contracting TB, she met her partner Esther Roper, who she went on to advocate and live with for the rest of her life. Together, they launched the sexual politics journal Urania, which worked to progress first-wave feminism and combat gender roles. [46]

Ronald Firbank (1886-1926) [chronic illness]

Image description: Ronald Firbank looks straight-faced into the camera in a black-and-white portrait, formally dressed. [49]

“The world is so disgracefully managed, one hardly knows to whom to complain.”

Ronald Firbank was a gay British novelist inspired by Oscar Wilde. Firbank wrote often on religion, sexuality, and social-climbing, and much of his work was shunned or left unpublished during his lifetime. He had chronic lung disease among other illnesses throughout his life. [50]

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) [chronic pain]

Image description: Frida Kahlo paints “Portrait of Frida’s Family,” while using assistive technology and laying on a bed. She wears her hair in a bun done up with ribbon and a child standing behind the bed gazes at her painting. A pot full of paintbrushes, stacks of books and papers, and a pile of pillows are visible in the background. [51]

“I don't give a s**t what the world thinks. I was born a b**ch, I was born a painter, I was born f***ed. But I was happy in my way. You did not understand what I am. I am love. I am pleasure, I am essence.” [52]

Frida Kahlo was a famous Mexican painter and bisexual woman with disabilities. She contracted polio as a child and was later involved in a car accident that damaged her pelvis and spine. [53] She lived with chronic pain and utilized assistive technology to create paintings from bed or wheelchair. She represented disability in multiple of her works and self-portraits, revealing how her experiences enriched her artwork.

Audre Lorde (1934-1992) [cancer]

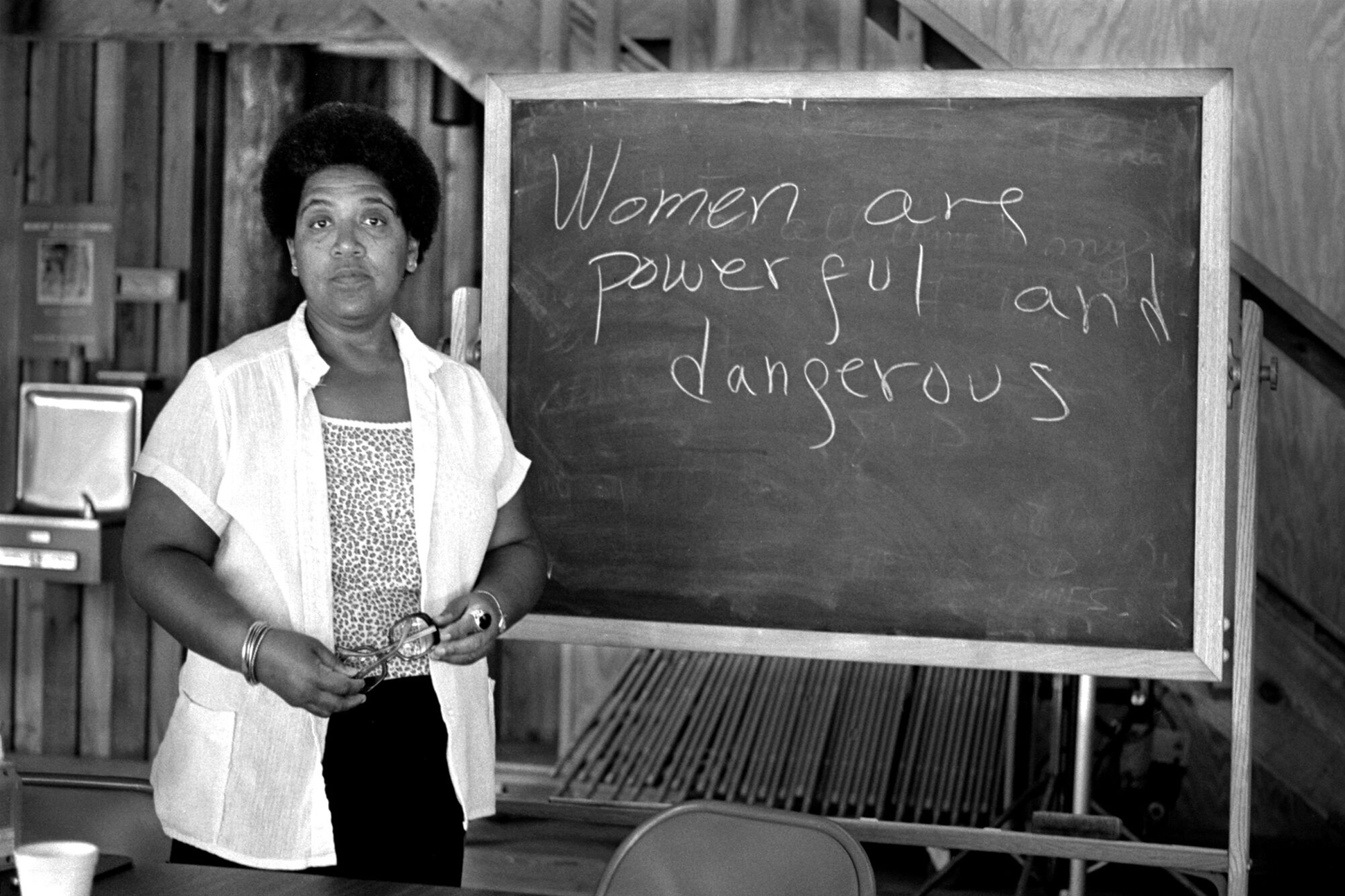

Image description: Audre Lorde stands in front of a chalkboard and looks into the camera with a straight face. The chalkboard reads, “Women are powerful and dangerous.”

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare." [54]

Audre Lorde was a Black lesbian feminist activist, poet, author, and teacher. Her work and wisdom on gender, sexuality, race, love, loss, life, disability, and education (and their many intersections) are foundational to a range of social movements. She did not explicitly identify as disabled, but explored disability and illness in The Cancer Journals (1980) and A Burst of Light (1988) in which she chronicled her breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Rather than ignoring pain and fear, she acknowledged, examined, and used them to better understand mortality as a source of power. This tendency to face and metabolize pain Lorde saw as a particularly African characteristic.Underlining the possibilities of self-healing, specifically the need to love her altered body, Lorde further stressed the importance of accepting difference as a resource rather than perceiving it as a threat. [55]

Barbara Jordan (1936–1996) [multiple sclerosis]

Image description: Barbara Jordan stands at a lectern during a speech and looks out into the audience, holding her arms extended to each side. She is wearing wire-rimmed glasses and a vest over a billowy long sleeve shirt.

“If the society today allows wrongs to go unchallenged, the impression is created that those wrongs have the approval of the majority.”

Barbara Jordan was a lesbian lawyer, educator, and Civil Rights leader who became the first woman elected to the Texas Senate, and the first black woman from the Deep South to be elected to US Congress. She sponsored over 70 bills to protect Civil Rights for marginalized communities. She lived with her partner, Nancy Earl for over 30 years. Jordan used a wheelchair during the later years of her career, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994. [56]

Pat Parker (1944–1989) [breast cancer]

Image description: Pat Parker stands at a microphone looking off into the audience with a confident straight look on her face. She is wearing a shirt, tie, and vest and gestures with one hand while speaking.

“If I could take all my parts with me when I go somewhere, and not have to say to one of them, ‘No, you stay home tonight, you won’t be welcome,’ because I’m going to an all-white party where I can be gay, but not Black. Or I’m going to a Black poetry reading, and half the poets are antihomosexual, or thousands of situations where something of what I am cannot come with me. The day all the different parts of me can come along, we would have what I would call a revolution.”

Pat Parker was a lesbian feminist poet and activist who had breast cancer. She was married twice to men, one of them physically violent, and began to identify as lesbian later in life. She was the executive director of the Feminist Women’s Health Centre, founded the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council, and helped form the Women’s Press Collective. She was strongly involved with the Black Panther Movement and campaigned for many different LGBTQ+ groups. [56]

Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992) [physical & psychiatric disabilities]

Image description: Marsha P. Johnson sits at a table smiling and holding a glass. She is wearing a pink dress, matching pink blush and eyeshadow, and a bouquet ring of flowers in her hair.

“How many years has it taken people to realize that we are all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race? I mean how many years does it take people to see that? We’re all in this rat race together!” [57]

Marsha P. Johnson was a Black trans woman famous for her critical role in the Stonewall uprising, and had both physical and psychiatric disabilities. Due to her multiple marginalized identities she was often wrongfully arrested and forced into medical treatments, which fed her drive for liberation from interconnected forms of oppression. [58] She co-founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with her friend Sylvia Rivera, which focused on trans and disability rights. She worked to stop forced psychiatric incarceration of LGBTQ+ people and put an end to conversion therapy. Her work was a cornerstone of the LGBTQ+ and Disability Rights movements today. [56]

Connie Panzarino (1947-2001) [Spinal Muscular Atrophy]

Image description: Connie Panzarino smiles at the camera, sitting in an electric wheelchair in a train station. She has long curly brown hair and pale skin; she wears silver glasses, dangly earrings, a patterned long sleeve shirt, a wooden beaded necklace, khaki pants, and has a tube connected to her neck and chin.

There's no decision here,

when

I can kiss for hours

without comin' up for air,

eat p*ssy,

grow tomatoes,

write books,

speak out,

and each day I survive

I become living testimony to the power of life.

[59]

Connie Panzarino was a lesbian activist living with Spinal Muscular Atrophy III. She founded Beechwood, a communal living environment for disabled women, where she worked as a therapist, writer, artist, and activist. She worked for legislative change for disabled people and was pivotal in lobbying for passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1963. In her 1994 autobiography, “The Me in the Mirror,” she detailed how her sexuality and disability intersected, and called out the rampant ableism of the LGBTQ community. [56]

Bobbie Lea Bennett (1947-2019) [physical disabilities]

Image description: Bobbie Lea Bennett is visible from the knees up in this black and white photograph. She sits in her wheelchair wearing a large trench coat with fur collar. Her right hand is resting on the padded foam of her wheelchair. Her left hand is curled near her face and left elbow rests on the wheelchair armrest. On both wrists she is wearing thin metal bracelets. She has round dark hair, pale skin, and she casually looks to her left with slightly open lips.

Bobbie Lea Bennett was the first woman to obtain gender affirmation surgery in 1978. She was told the cost would be covered under Medicare’s Social Security disability benefits program, but it was not. So, she mobilized her community to force Medicare officials to consider gender affirmation surgeries as medical necessities. After driving to the office of Medicare director Thomag Tierney and refusing to leave, she received the reimbursement she was owed, although Medicare officials denied that the money was to cover gender-affirmation surgery. She founded the St. Tammany Organization for the Handicapped, and hosted "Barbie's Talk Show", a community television program to raise awareness of physical accessibility issues. [55, 58, 60]

Morty Manford (1950-1992) [psychiatric disabilities and HIV]

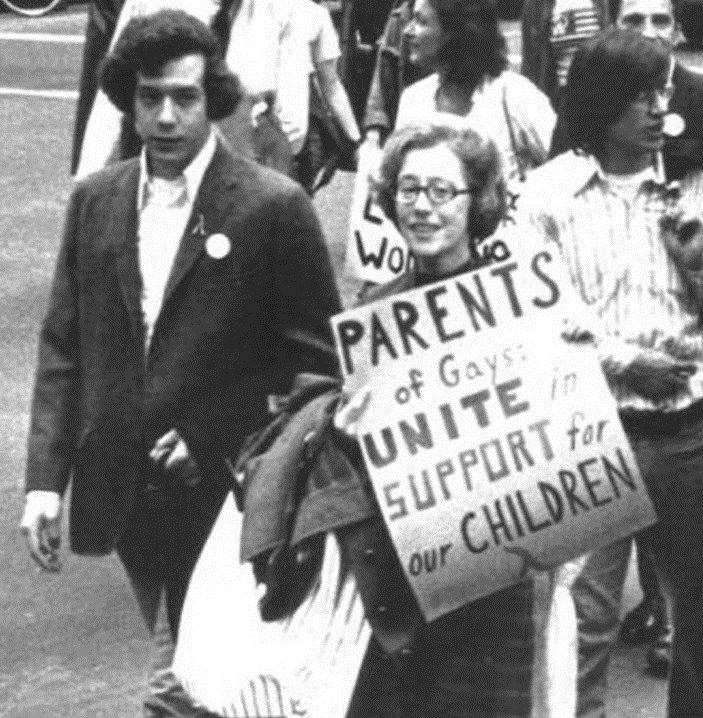

Image description: Morty Manford (left) and his mother Jeanne Manford (right) walk side by side at a gay liberation march, with a crowd visible behind them. Morty wears a suit with two pins on it, and has dark curly hair. Jeanne has short blonde hair and wears glasses and dark clothing, and carries a sign that reads, “Parents of gays unite in support for our children.”

Morty Manford was a gay activist with psychiatric disabilities who was known for his presence at the Stonewall riots, where he his horrific physical assault by Michael Maye garnered public attention. Morty co-founded the gay rights organization PFLAG with his mother Jeanne Manford, and helped found Gay People at Columbia University, one of the first gay campus organizations in the US. He was also heavily engaged with Gay Activists Alliance, and is remembered today for his advancement of human rights in the LGBTQ+ community. [55]

Jazzie Collins (1958–2013) [HIV]

Image description: Jazzie Collins is pictured from the chest up, looking at the camera with slightly open lips. She has curly auburn hair and medium brown skin; she wears burgundy wire glasses, a cream colored shirt with sunglasses hanging on the neck, a brown cardigan, gold circular earrings, a knit black hat with a bill, a brown leather purse over her shoulder.

"When our queer youth cannot use public open space and are homeless, criminalized and incarcerated for no reason, we say we will not tolerate any form of discrimination against anyone in the city and county of San Francisco. Occupy everything!"

Jazzie Collins was a trans woman living with HIV based in San Francisco who was an advocate for disabled people, people of color, and queer and trans people of color of all ages. She worked for housing, food, health, and worker justice, running the food pantry 6th Street Agenda and being one of the original members of Queers for Economic Equality Now (QUEEN). With QUEEN, she organized protests and the city’s annual Trans March, and was the Vice Chair of the LGBT Aging Policy Task Force, Vice Chair of the LGBT Senior Disabled Housing Task Force, and active in Senior and Disability Action. [46]

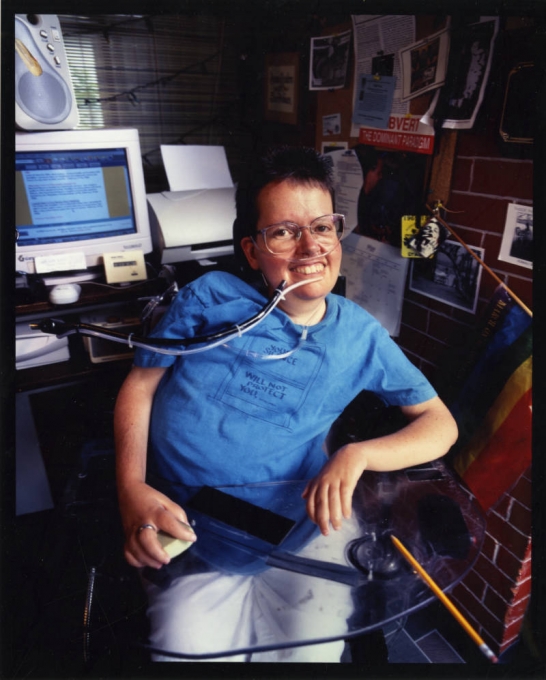

Laura Hershey (1962-2010) [Spinal Muscular Atrophy]

Image description: Laura Hershey sits in her wheelchair and smiles at the camera in front of a desk with a computer and papers and a rainbow flag posted on the wall behind her. She is wearing a blue shirt, gray pants, glasses, and a nasal cannula. [61]

Remember, you weren’t the one

Who made you ashamed,

But you are the one

Who can make you proud.

Just practice,

Practice until you get proud, and once you are proud,

Keep practicing so you won’t forget.

You get proud

By practicing. [62]

Laura Hershey was an author and disability and LGBTQ+ activist. As a child she was featured in multiple Telethon charity ads and she later spoke out against such fundraisers portraying people with disabilities as the “cheerful victim.” She directed the Denver Coalition for People with Disabilities, led the Disability Center for Independent Living, and co-founded the Domestic Alliance Initiative. She worked often with government and municipalities to promote accessibility through the Americans with Disabilities Act and LGBTQ+ rights. [61]

Mel Baggs (1980-2020) [Autism and multiple physical and neurological disabilities]

Image description: Mel Baggs sits on a couch typing on a laptop while looking off to the right. Sie is wearing a white shirt and olive pants and there is a white and tan spotted dog sitting on the couch next to hir, and a stuffed animal behind hir. [63]

“Only when the many shapes of personhood are recognized will justice and human rights be possible.”

Mel Baggs was a genderless autistic writer and activist famous for hir video, “In My Language” which honors and validates diverse forms of communication and interaction with others and the world. Sie spoke out against the stereotypes of autism portrayed by the Getting the Word Out Campaign of the Autism Society of America, and wrote prolifically in hir blogs Cussin’ and Discussin’ [64] and Ballastexistenz [65]. Sie was a bastion of the neurodiversity movement and fought for the rights of people with disabilities to care, support, expression, and agency. [63]

Stacey Milbern (1987-2020) [Muscular Dystrophy]

Image description: Stacey Milbern speaks into a microphone someone holds up to her mouth. She covers her trach with one finger while sitting in her wheelchair, and wears yellow glasses and a green shawl over a blue jacket. Behind her are protest signs, one in the shape of a flame and another shaped like a rectangle with red text that reads, “Power to the People. PG&E is killing us for profit.”

“Oftentimes, disabled people have the solutions that society needs. We call it crip - or crippled - wisdom.” [66]

Stacey Park Milbern was a queer disabled activist and writer with muscular dystrophy. She wrote pieces and led efforts for disability justice and co-produced the Crip Camp Impact Campaign [67] alongside Andraéa LaVant, including a series of seminars on often overlooked disability justice topics to increase the reach of the movie, Crip Camp. She founded Disability Justice Culture Club with friends, and with them and other collectives engaged in mutual aid and advocacy to support people with disabilities and those in need during COVID-19. [68]

Ki’tay D. Davidson (1992-2014) [Autism]

Image description: Ki’tay Davidson smiles into the camera while wearing a backpack and gray striped shirt. Behind him are green trees and a walkway to an ocean with a gravel shore.

“I want to believe we can unlearn violence & affirm our interdependency. I dream of a community of lovers, who navigate pain, joy, laughter and grief together, collectively & with care; experiencing endless beauty.”

Ki’tay Davidson was a trans activist with ASD who wrote, spoke, and acted for racial justice, gender justice, disability justice, and trans liberation, among others. He co-created the hashtag #DisabilitySolidarity. Ki'tay intentionally centered people and communities who are most marginalized by and in our society. who co-created the hashtag #DisabilitySolidarity. The White House honored him as a 'Champion of Change for embodying the next generation of leadership within the disability community and his commitment to the promise of the Americans with Disabilities Act. [69]

Works Cited

Seneca Falls Historical Society. (1908). Celebration of the 60th anniversary of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention [black & white photograph]. Seneca Falls Historical Society, Seneca Falls, NY. https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll96/id/21/rec/2

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Today in History - July 19. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/july-19.

Baynton, D. C. (2001). Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History. In P. K. Longmore & L. Umansky (Eds.), The New Disability History: American Perspectives (pp. 33-57). New York University Press. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1396403/files/68152678/download?download_frd=1.

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). 14th Amendment. Cornell Law. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/amendmentxiv.

Curie, N. (2020, June 29). William Dorsey Swann, the Queen of Drag. Rediscovering Black History. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2020/06/29/william-dorsey-swann-the-queen-of-drag/.

Block, M. (2020, August 17). The Nudge And Tie Breaker That Took Women's Suffrage From Nay To Yea. The Public Radio Service of Western Kentucky University. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://www.wkyufm.org/post/nudge-and-tie-breaker-took-womens-suffrage-nay-yea#stream/0.

National Archives. (2021, August 3). 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Women's Right to Vote. National Archives. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/19th-amendment.

Goodman, E. (2018, June 27). 6 Major Moments in Queer History BEYOND the Stonewall Riots. Them. Retrieved November 20, 2021 from https://www.them.us/story/queer-history-beyond-stonewall.

Sarran Webster, E. (2019, June 3). 20 Historic Moments in the Fight for LGBTQ Rights. Teen Vogue. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.teenvogue.com/story/lgbt-equality-key-moments-timeline.

Fuchs, E. (2013, March 27). The Supreme Court Actually Ruled For Gay Rights More Than 50 Years Ago. Business Insider. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.businessinsider.com/one-inc-v-olesen-2013-3.

Blake, J. (2019, January 21). A new Supreme Court is poised to take a chunk out of MLK's legacy. CNN. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/20/us/mlk-legacy-supreme-court/index.html.

National Archives. (2018, April 25). The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. National Archives. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/civil-rights-act.

Voting Rights Act (1965); An act to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States and for other purposes, August 6, 1965; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=100.

Farber, J. (2016, April 20). Before the Stonewall Uprising, There Was the ‘Sip-In’. New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/21/nyregion/before-the-stonewall-riots-there-was-the-sip-in.html?_r=0.

Simon, S. (2008, June 28). Remembering a 1966 'Sip-In' for Gay Rights. Weekend Edition Saturday on NPR. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=91993823.

Editors, H. (2010, October 18). The Stonewall Riots begin in NYC’s Greenwich Village. History.com. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-stonewall-riot.

Rights, Civil. (2009, June 22). Stonewall Riots: The Beginning of the LGBT Movement. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.civilrights.org/archives/2009/06/449-stonewall.html.

Parenthood, Planned. (2014, January). ROE V. WADE: ITS HISTORY AND IMPACT. Planned Parenthood. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/files/3013/9611/5870/Abortion_Roe_History.pdf.

DREDF. (n.d.). Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://dredf.org/legal-advocacy/laws/section-504-of-the-rehabilitation-act-of-1973/#:~:text=Section%20504%20of%20the%201973,the%20Americans%20with%20Disabilities%20Act.

Trainer, M. (2017, April 10). How 150 Americans took over a building and changed disability law. Share America. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://share.america.gov/how-150-americans-changed-disability-law/.

Cone, K. (n.d.). Short History of the 504 Sit-in. Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://dredf.org/504-sit-in-20th-anniversary/short-history-of-the-504-sit-in/.

Hershey, L. (2004). LGBT History: Disability, Disabled People, and Disability Movements. Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History in America (Volume 1). Omnilogos. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://omnilogos.com/lgbt-history-disabled-people-and-disability-movements/.

Ervin, M. (2020, July 1). An Oral History of the Capitol Crawl. New Mobility. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://newmobility.com/the-capitol-crawl/.

Little, B. (2020, July 24). When the 'Capitol Crawl' Dramatized the Need for Americans with Disabilities Act. History.com. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.history.com/news/americans-with-disabilities-act-1990-capitol-crawl.

Parrott-Sheffer, C. (n.d.). Americans with Disabilities Act. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Americans-with-Disabilities-Act.

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 328 (1990). Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq9805.html

ADA.gov. (n.d.). Introduction to the ADA. ADA.gov. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.ada.gov/ada_intro.htm.

NYC, Disability Pride. (n.d.) Our History. Disability Pride NYC. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://disabilitypridenyc.org/our-history/.

Triano, S. (n.d.) What is Disability Pride? Disability Pride PA. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://disabilitypridepa.org/whatisdisabilitypride.

Goodman, A. (2000, April 27). Vermont Civil Union Bill Becomes Law. Democracy Now. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.democracynow.org/2000/4/27/vermont_civil_union_bill_becomes_law.

Obama Signs Matthew Hudson, W. (2009, October 28). Obama Signed Matthew Shepard/James Byrd Hate Crimes Bill into Law. Bilerico Report on LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://bilerico.lgbtqnation.com/2009/10/obama_signs_matthew_shepardjames_byrd_hate_crimes.php.

Strasburger, C. (2015, April 9). How a Trans Teen Inspired the President to Make a MAJOR Change. Teen Vogue. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://www.teenvogue.com/story/leelahs-law-political-change.

Sequenzia, A. (2016, April 27). Autistic Conversion Therapy. Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://awnnetwork.org/autistic-conversion-therapy/#.

Evans, D. (n.d.). Marriage Equality. Center for Disability Rights. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://cdrnys.org/blog/disability-dialogue/the-disability-dialogue-marriage-equality/.

Obergefell, J. (n.d.) Jim Obergefell | News & Commentary. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.aclu.org/news/by/jim-obergefell/.

Haug, O. (2021, October 27). America’s First Gender-Neutral Passport Has Finally Been Issued. Them. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.them.us/story/americas-first-gender-neutral-passport-finally-been-issued.

Rahaman Sarkar, A. (2021, October 29). ‘Awesome moment’: Dana Zzyym celebrates as first American with an ‘X’ gender passport. Independent. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/first-gender-x-passport-dana-zzyym-b1947494.html.

TFTEF. (n.d.). Who is Frances Thompson?. The Frances Thomspon Education Foundation. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.tftef.org/about-2.

Art Barn Festival. (n.d.) Frances Thompson. Art Barn Festival. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://artbarnfestival.wordpress.com/portfolio/frances-thompson/.

Brennan, S. (2011, February 11). Frances Thompson: Honoring Black Survivors Who Forged the Path Before Us. Zacharias Center. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://zcenter.org/blog/frances-thompson/.

Ore, J. (2020, February 28). America's first drag queen was a former slave and LGBT rights crusader, says historian. CBC News. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.cbc.ca/radio/day6/teck-frontier-mine-medical-assistance-in-dying-1990s-mls-wilson-cruz-the-first-drag-queen-and-more-1.5477892/america-s-first-drag-queen-was-a-former-slave-and-lgbt-rights-crusader-says-historian-1.5478181.

Joseph, C. (2021, October 13). America's Black Queer History: Wiliams Dorsey Swann. The American Academy in Berlin. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.americanacademy.de/videoaudio/americas-black-queer-history/.

Richards, P.L. (2008, September 6). September 6: Jane Addams (1860-1935). Disability Studies, Temple U. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from http://disstud.blogspot.com/2008/09/september-6-jane-addams-1860-1935.html.

Brubaker, J. (2004) "Jane Addams." Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 23, pp. 1-9.

Fradin, J. B. and D. B. Fradin. (2006). Jane Addams: Champion of Democracy. New York: Clarion Books.

Elliott, L. (2018, March 29). Part Three: The Badass Disabled LGBTQ+ Women History Forgot. Medium. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://lcelliott2.medium.com/part-three-the-badass-disabled-lgbtq-women-history-forgot-2f10e78bfbbe.

Field, M. (1908). It was deep April. Victorian Queer Archive. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://vqa.dickinson.edu/poem/it-was-deep-april.

Foundation, Poetry. (n.d.). Eva Gore-Booth. The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/eva-gore-booth.

New Directions Books. (n.d.). Ronald Firbank. New Directions Books. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.ndbooks.com/author/ronald-firbank/.

Rutledge, S. (2020, January 17). #QueerQuote: “The World is Disgracefully Managed, One Hardly Knows to Whom to Complain. – Ronald Firbank. The WOW Report. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://worldofwonder.net/queerquote-the-world-is-disgracefully-managed-one-hardly-knows-to-whom-to-complain-ronald-firbank/.

Herstik, G. (2017, July 6). 11 things you may not know about Frida Kahlo, in honor of la reina's birthday. Hello Giggles. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://hellogiggles.com/lifestyle/didnt-know-frida-kahlo-birthday/.

Saati, B. (2013, June 12). M+V Art Brings Never Before Seen Frida Kahlo Photographs to Miami. Miami New Times. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.miaminewtimes.com/arts/m-v-art-brings-never-before-seen-frida-kahlo-photographs-to-miami-6500304?showFullText=true.

Appelbaum, L. (2018, June 5). Frida Kahlo: Role Model for Artists, People with Disabilities and Bisexual Women. RespectAbility. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.respectability.org/2018/06/frida-kahlo-lgbt-pride-month/.

Lorde, A. (2017) A Burst of Light: and Other Essays. AK Press.

Ortiz, C. (2020). 9 Disabled Activists from the Queer Rights Movement. Disability Pride 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://sites.duke.edu/disabilitypride2020/artwork/queer-rights/.

Brownworth, V. A. (2020, October 20). The Intersection Of LGBTQ History And Disability. Philadelphia Gay News. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://epgn.com/2020/10/20/the-intersection-of-lgbtq-history-and-disability/.

Cheung, C. (2020, June 28). It’s Pride Month!: Remembering Marsha “Pay It No Mind” Johnson. Youth Be Heard. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://youthbeheard.org/2020/06/28/its-pride-month-remembering-marsha-pay-it-no-mind-johnson/.

Ellison, J.M. (2018, June 14). 4 Activists Who Make Me Proud to be Disabled and Transgender. Rooted in Rights. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://rootedinrights.org/4-activists-who-make-me-proud-to-be-disabled-and-transgender/.

Panzarino, C. (1994). The Me in the Mirror. Seal Press.

Matte, N. (2014). Historicizing Liberal American Transnormativities: Medicine, Media, Activism, 1960-1990. University of Toronto.

Denver Public Library. (n.d.). Laura Hershey (1962 - 2010). Denver Public Library. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://history.denverlibrary.org/colorado-biographies/laura-hershey-1962-2010.

Hershey, Laura. (2014, December 1). Poem by Laura Hershey: “You Get Proud By Practicing”. Disability Visibility Project. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2014/12/01/poem-by-laura-hershey-you-get-proud-by-practicing/

Genzlinger, N. (2020, April 28). Mel Baggs, Blogger on Autism and Disability, Dies at 39. New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/health/mel-baggs-dead.html.

Biggs, M. (n.d.). Cussin' and Discussin' – Mel being human in a world that says I'm not. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://cussinanddiscussin.wordpress.com/.

Biggs, M. (n.d.) Ballastexistenz. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://ballastexistenz.wordpress.com/.

Genzlinger, N. (2020, June 6). Stacey Milbern, a Warrior for Disability Justice, Dies at 33. New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/06/us/stacey-milbern-dead.html.

Crip Camp. (2020). The Official Virtual Experience. Crip Camp. Retrieved November 2021 from https://cripcamp.com/officialvirtualexperience/.

Disability Visibility Project. (2020, May 19). Loving Stacey Park Milbern: A Remembrance. Disability Visibility Project. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2020/05/19/loving-stacey-milbern-a-rememberance/.

YO! Disabled & Proud. (2019, June 25). Celebrating the Legacy of Ki’tay D. Davidson. YO! Disabled & Proud. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://yodisabledproud.org/blog/celebrating-the-legacy-of-kitay-d-davidson/

Raine, S. (2012, February) Federal Sterilization Policy: Unintended Consequences. AMA Journal of Ethics. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/federal-sterilization-policy-unintended-consequences/2012-02

Justia. (n.d.). Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349 (1978). Justia. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/435/349/

Sonneborn, L. (n.d.) Disability Rights Timeline. Temple University. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://disabilities.temple.edu/resources/disability-rights-timeline

NAD. (n.d.) Oldest Civil Rights Organization in the U.S. NAD. Retrieved on December 8, 2021 from https://www.nad.org/oldest-civil-rights-organization-in-the-us/

NFB. (n.d.) History and Governance. NFB. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://nfb.org/about-us/history-and-governance

Global Down Syndrome Foundation. (n.d.) Down Syndrome Human and Civil Rights Timeline. Global Down Syndrome Foundation. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://www.globaldownsyndrome.org/about-down-syndrome/history-of-down-syndrome/down-syndrome-human-and-civil-rights-timeline/

NILP. (2020). The History of the Independent Living Movement. NILP. Retrieved December 8, 2021 from https://www.nilp.org/history-of-independent-living-movement/

Gershon, L. (2021, September 3). The Ugly History of Chicago’s “Ugly Law.” JSTOR Daily. Retreived December 8, 2021 from https://daily.jstor.org/the-ugly-history-of-chicagos-ugly-law/

Uyeda, L. (2021, May 26). How LGBTQ+ Activists Got “Homosexuality” out of the DSM. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved December 9, 2021 from https://daily.jstor.org/how-lgbtq-activists-got-homosexuality-out-of-the-dsm/

Whalen, K. (n.d.). (In)Validating Transgender Identities: Progress and Trouble in the DSM-5. National LGBTQ Task Force. Retrieved December 9, 2021 from https://www.thetaskforce.org/invalidating-transgender-identities-progress-and-trouble-in-the-dsm-5/

People First. (n.d.) History of People First. People First. Retrieved December 9, 2021 from http://peoplefirstwv.org/old-front/history-of-people-first/#:~:text=The%20first%20People%20First%20Convention,began%20to%20grow%20and%20spread.&text=Today%2C%20People%20First%20and%20the,estimated%2017%2C000%20members%20or%20more.

IDEA. (2020, November 24). A History of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/IDEA-History